Greece

Although Crete hosts one-quarter of Greece’s annual visitors, it’s still possible to escape the crowds by heading south. Thanks to the rugged mountains that stretch across much of the island’s spine, southern Crete remains a place apart.

Although Crete hosts one-quarter of Greece’s annual visitors, it’s still possible to escape the crowds by heading south. Thanks to the rugged mountains that stretch across much of the island’s spine, southern Crete remains a place apart.

Known for their hospitality, traditional music and healthy home-cooking, Cretans are also fiercely independent. They frequently rebelled under Venetian and then Ottoman occupation, with southern strongholds like Sfakia (a rocky, barren territory centred on port village Hora Sfakion) remaining unconquered.

Due to the towering cliffs overhanging the sea, the Sfakia area remains peacefully isolated; nearby settlements like Loutro, shimmering white with houses, or Sweetwater and Marmara (Marble) beaches are accessible by boat (the intrepid can hike there instead). Boat trips hug the coast westward from Hora Sfakion to Paleohora, via Loutro and Agia Roumeli; the latter is where throngs of tired hikers stumble out of the Samaria Gorge – at 16km, Europe’s longest. This boat trip is ideal for traversing the south coast. It concludes at Paleohora – a small town that has preserved its laid-back character, despite being the jumping-off point for popular Elafonisi Beach on Crete’s southwestern tip. The soft pink sands and islet here are undeniably enticing and, except for in high summer, serene. Palaeohora also offers great live traditional music; the songs, known as mantinades (15-syllable folk verse accompanied by the Cretan lyra, or violin), fully express the island’s powerful and melancholy spirit.

Crete is big enough to be its own country, and its people love distinguishing themselves from other Greeks. Lakkis Koukoutsakis, a young tour guide/restaurant owner in Azogires, a placid hamlet seven kilometres north of Paleohora, sums it up: ‘among us here live about 13 Cretans, eight Greeks, two English and one Dutch’, he quips. It is this sense of otherness (amply displayed in Lakkis’ splendidly curling, pencil-thin moustache – a relic of centuries past), that makes the Cretans, and especially those from the south, such good company. They can entertain with eccentricity or anecdotes, vex with their stubbornness, seduce with hospitality and amaze with feats of strength. It goes without saying that being among them is rarely dull.

The southern mountains are dotted with tiny traditional villages, fantastic spots to buy hearty local olive oil and thyme honey, though Azogires has a freshwater lagoon where the itinerant nereids – those beguiling sea-nymphs of ancient Greek myth – can allegedly steal a man’s soul on one sacred night each year. More otherworldly characters – the so-called drosoulites, or ghosts of fighters killed by the Turks in 1828 – can apparently be seen marching around dawn each year in late May, over at Frangokastello. This magnificent 13th-century Venetian fortress stands above a tranquil beach east of Hora Sfakion. Occasional yoga groups visit Azogires, though unruffled Agios Pavlos, further east on the south coast, is more established. Just three kilometres west, the outpost of Triopetra comprises barely one set of domatia (rooms for rent) complemented by a seafront terrace restaurant. Here, all sense of time quickly recedes, and the menu varies according to the catch of the day. Keenly aware of the irreplaceable value of Triopetra (where some regular visitors book rooms three years ahead), locals protested vociferously when a Chinese consortium sought to build a huge container ship port – as ever through the centuries the Cretans stubbornly resisted a much bigger foreign foe.

Triopetra’s relative inaccessibility and tiny size have kept it blissfully quiet. Yet even the places that attract more visitors, such as lazy Plakias, west of Preveli, stand apart from the north and its resorts. Having one of the south’s longest beaches, Plakias has attracted some smallish hotels and restaurants, though the truly extraordinary Youth Hostel Plakias (open from Greek Easter through October) also attracts devotees of all ages.

One of the reasons why Plakias and other southern getaways have remained relatively immune from mass tourism is the terrific summer wind that roars through everything, pelting beach-goers with sand and whipping up whitecaps on the sea. But the winds also drive away the mosquitoes, and break through that solid wall of summer heat. Channelled up and down Crete’s mountain canyons – veritable wind tunnels – these stiff breezes are known to locals by individual names, depending on from where they come, how long they stay, and what gifts they bring with them.

Good but winding paved roads connect the south-coast towns, where the terrain allows. Regular buses run from the north-coast hubs of Hania and Rethymno to Paleohora, Hora Sfakion and Plakias. The website www.sfakia-crete.com offers local information, including timetables for the Hora Sfakion-Paleohora ferries.

Read more: http://www.lonelyplanet.com/greece/crete/travel-tips-and-articles/75819##ixzz2XP09cfuv

https://www.jenreviews.com/best-things-to-do-in-greece/

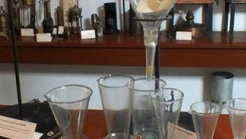

The museum Crete chemistry, is in operation since 1996 and is hosted in building the State Laboratory of Chania.

__list_246_139_c1.jpg)

The Military Museum of Rethymno is situated on the southern tip of the Municipal district of the village of Chromonastery , 11klm southeast of Rethymno and on the northern rims of mountain Vrysinas, at an altitude of 360m. From a historical viewpoint, Chromonastery is one of the most remarkable hist

Loutro is a picturesque fishing village in the Sfakia prefecture, accessible via boat from Sfakia.Life here moves at a slow pace, fishing, chatting and swimming at the nearby beaches.

1039 Ε 6061 01515 00